“The way Elvis destroyed himself interests me, because

I don’t ever want to walk those grounds myself.”

Michael Jackson, "Moon Walk" (1988)

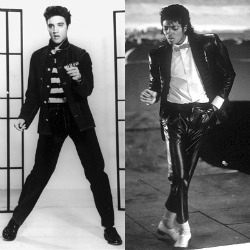

But apparently the King of Pop changed his mind about The King of Rock, the father-in-law he never met.

On MySpace, Lisa Marie Presley recalled how one day in 1993, her husband told her “with an almost calm certainty, ‘I am afraid that I am going to end up like him, the way he did.” The King’s daughter concluded: “The exact scenario I saw happen on August 16th, 1977, happened again with Michael just as he predicted.”

Who else might have foreseen that such a bright star, in his attempt to surpass even Elvis, would become so much like him that he would suffer the same tragic fate?

Who else might have foreseen that such a bright star, in his attempt to surpass even Elvis, would become so much like him that he would suffer the same tragic fate?

From the beginning of his career at age 6, “I dreamed of creating the biggest-selling record of all time,” Michael wrote. He achieved this goal in 1984 with his historic “Thriller.” But his appetite for the throne was only whetted.

“If Elvis is supposed to be the King, what about me?” he would often say. Then, in 1989, after his chart-topping Bad, Michael was proclaimed the “King of Pop.” But he still felt he hadn’t surpassed the King of Rock.

“The most important thing to him was his legacy,” declared his longtime manager, Bob Jones. “He feared the fates of Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis, Jr … Michael desired to be remembered and worshipped like Elvis.”

The future King of Pop had met the King of Rock and his daughter in late 1974 while performing with the Jackson Five in Las Vegas. Michael, 16 then, was on his way up; Elvis, pushing 40 and terminally addicted, was on his way down.

Elvis's drug habit had begun for professional reasons: he took speed in the late fifties to keep up his exhausting national tours. Michael started taking painkillers to endure his own demanding schedule after his Pepsi burn accident.

Both stars were blessed and cursed with an unstoppable, all-consuming drive. The once poor boy from Tupelo called ambition “a dream with a V8 engine,” and the once poor boy from Gary would surely have agreed. The superhuman aspirations of both kings had originally been spurred by two musical visionaries.

Sam Phillips, the Sun records head who recorded Elvis’s break-out hit, “That’s Alright,” had famously remarked: "If I could find a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars."

Berry Gordy, the Motown records head who discovered the Jackson Five, told the brothers he would make them “the biggest thing in the world.” Michael recalled: “I’ll never forget that… it was like a fairy tale come true.”

Indeed, the kings grew up on make-believe.

When receiving the Ten Outstanding Young Men of the Nation Awards, Elvis told the crowd that he had always been the hero of every comic book he read so insatiably as a boy. “Every dream I ever dreamed has come true a hundred times,” he concluded.” His hero was Captain Marvel. On stage the King wore the superhero’s cape and a golden thunderbolt necklace.

The Man Who Murdered Jimi Hendrix?

Michael said he was “a fantasy fanatic,” and “not to crazy about the reality of things.” At age 44, the King of Pop told BBC’s Martin Bashir that he was Peter Pan.

“No you’re not. You’re Michael Jackson,” Bashir reminded him.

The ageless star and architect of Neverland, more fantastic than Graceland itself, replied: “I’m Peter Pan in my heart.”

The ageless star and architect of Neverland, more fantastic than Graceland itself, replied: “I’m Peter Pan in my heart.”

Both boy kings lived by the same credo: If you believe with all your heart, anything can come true. This childlike faith came from their beloved, southern Baptist mothers: Gladys from Mississippi, and Katherine — who later became a Jehovah’s Witness — from Alabama.

The fathers of the two mothers’ boys were firm realists. Elvis had little respect for Vernon, a sharecropper and moonshiner, but later hired him as his financial manager. Michael feared and hated Joe, a crane operator and frustrated musician who managed his five sons with merciless purpose.

The Media's 'Ground Zero Mosque' Follies

“There are winners and losers in this world,” he would lecture them, belt in hand, “and you’re going to be winners!”

But, in striving to become not just a winner, but a superstar bigger than Elvis himself, Michael felt unfairly handicapped. According to Vanity Fair’s Maureen Orth, he complained to his managers that record stores carried Elvis but few black artists. He added that the industry had “conspired” against him “after I broke Elvis’s sales and the Beatles’ sales.”

“They don’t give me my due because I’m black,” biographer Darwin Porter, quoted the star as saying. “So maybe I’ll try to become white.” Critics accuse him of having done exactly that, calling him “Wacko Jacko,” for this and other presumed oddities, and professionally hobbling him further.

Elvis, whose ID bracelet read “CRAZY,” had weathered his share of criticism too. Detractors dubbed him “Elvis the Pelvis,” the Catholic church denounced his music, and Frank Sinatra himself called it a “rancid-smelling aphrodisiac."

In spite of their great personal differences, the kings became mirror images in their extravagances, excesses, ailments, and their struggles with the pressures of superfame. They gave away Cadillacs, houses, and donated millions to charities. They were shopaholics and built fairytale Camelots. And they spent kings’ ransoms on prescription steroids, sedatives, and painkillers to treat their increasing ailments, most stress-related.

Both were tortured with severe migraine headaches and insomnia. In drug-induced half sleep, they had nightmares of being murdered, triggered by the death threats they received regularly. Both were diagnosed with Lupus, pleurisy, immune deficiency, anemia and glaucoma.

The kings’ favorite pain reliever became Demerol, then Oxycontin. Elvis doctor-shopped and amassed coast-to-coast drug enablers. Michael used two of them himself — Dr. George Nichopoulos and Dr. Elias Ghanem. Prescriptions were written for the kings using pseudonyms and the names of their handlers. In the end, both were playing Russian roulette: Elvis with Dilaudid, a super-strength morphine used for terminal cancer patients; Michael with Propofol, used for general anesthesia.

A few years before his final sleep, the King of Pop confided to his friend and spiritual advisor, Dr. Deepak Chopra, that he had found something “that takes you to the valley of death and then takes you back." The new age guru was horrified and, with Michael’s other spiritualist friend, Uri Geller, begged him to seek help. Under duress, the star had entered rehab twice. Otherwise he refused the repeated intervention attempts by his own brothers.

Elvis, too, had detoxed numerous times and fallen off the wagon. His own spiritual advisor, Larry Geller, and his bodyguards — old school friends whom he called brothers — tried to intervene. But, according to biographers, Thompson and Cole (“The Death of Elvis: What Really Happened”), he raged, “I’ll buy the goddamned drugstore if I have to. I’m going to get what I want. People have to realize either they’re for me or against me!”

The King fired his beloved bodyguards, replacing them with his young step-brothers who became addicted themselves. In desperation, his father, Vernon, and his manager, Colonel Parker, begged his ex-wife to intervene and get him help. But Priscilla failed too.

It was déjà vu for their daughter, Lisa Marie, who married Michael seven months after his first detox. "I became very ill and emotionally/spiritually exhausted in my quest to save Michael from certain self-destructive behavior,” she wrote. Before they were divorced, he had begged her to join him in a séance to reach Elvis.

Before their untimely deaths, the King of Rock and the King of Pop — though one had become a behemoth and the other skeletal –had become much the same person. Both were on the verge of bankruptcy. Both were being called has-beens.

Elvis was about to return to the road, but feared he hadn’t the strength. At the end of his previous tour, after his grand Thus Spake Zarathustra entrance, he had collapsed on stage, wept, and been carried out. “My life is over. I’m a dead man!” he told his step-brother and biographer, David Stanley (“Raised on Rock”) after his bodyguards published a tell-all (“Elvis: What Happened?”) revealing him as terminally addicted.

Michael, on the brink of a comeback tour himself, had collapsed during a Staples rehearsal. “It’s over … I’m better off dead,” he told one of his handlers, according to biographer Ian Halperin.

The last enabler of each king — Dr. Conrad Murray for Michael, Dr. George Nichopoulos for Elvis — unsuccessfully performed CPR. The family of each star blamed his physician for the tragedy. Nichopoulos was tried for manslaughter and exonerated, but was suspended from medical practice. Murray will also be tried for manslaughter, and may lose his license, too.

Near the end, the King wrote the epitaph for himself, as well as for his son-in-law: “The image is one thing and the human being is another, it's very hard to live up to an image.”

Making the Case Stick Against Dr. Murray