Here I continue my discussion with R.J. Ryan and Daniel Quantz, the writers now talk about SYNDROME published by Archaia.

Read the first part of the interview here.

About SYNDROME, how did you come up with this story?

About SYNDROME, how did you come up with this story?

RJR: SYNDROME was a writing assignment that turned, out of necessity, into a labor of love. If we hadn't given this book our all, it would show and the book would suck. Hard. A company called Fantasy Prone, which had really only done one other comics series which was written by the company's owner, Blake Leibel, had approached us to work on some TV development based on what was a very incomplete idea — just the basic notion of a serial killer being treated by a "House"-like character in an insane asylum.

DQ: It was, essentially, the title character from “House” working in a hospital for the criminally insane squaring off against Hannibal Lecter types. Essentially, it was a provocative seed of an idea that was unfortunately pretty derivative on the surface. In real estate terms, it was a unique fixer-upper

RJR: Blake and Fantasy Prone have a lot of irons in the fire, with a big focus on producing animation for television and other projects that are aimed at younger audiences than SYNDROME. They were looking to hand this idea off to us so that Blake could focus on the comics he actually writes and scripts himself — a series called "United Free Worlds" which has been around for a few years and has a significant following with really little boys, like 7-9 year olds. It's filled with fighter jets and dinosaurs and bloodthirsty barbarians and exploding planets — far-out stuff, but not really our kind of thing.

RJR: Blake and Fantasy Prone have a lot of irons in the fire, with a big focus on producing animation for television and other projects that are aimed at younger audiences than SYNDROME. They were looking to hand this idea off to us so that Blake could focus on the comics he actually writes and scripts himself — a series called "United Free Worlds" which has been around for a few years and has a significant following with really little boys, like 7-9 year olds. It's filled with fighter jets and dinosaurs and bloodthirsty barbarians and exploding planets — far-out stuff, but not really our kind of thing.

At the time of our first meeting on SYNDROME, early last year, we were not available to start development work. We were engaged on another project and had like three months left of work on that. By the time we did become available, the guys at Fantasy Prone had decided it might be better to pursue this type of idea as a comic book that could, down the road, have some transmedia potential. We agreed but we're fairly picky about what kind of comics work we do, so we did insist on a significant chunk of ownership in the property and we demanded a level of creative freedom that you simply can't get in company-owned comics at Marvel or DC. Fantasy Prone and eventually Archaia, the book's publisher, allowed us to really cut loose and change just about everything about the original idea, which was great. Of course, what we came up with was much more high concept and less reliant on movies and TV shows that have come before. Archaia likes selling this as "the Truman Show" with serial killers, but that kind of ignores half the book, which is a pretty in-depth character study of four individuals caught up in a giant, bizarre experiment — each with their own complicated motivations for being there. We should say we knew our take was one that the people at Fantasy Prone and Archaia would respond to a lot more than the logline with which we were presented.

DQ: When we heard they wanted to do SYNDROME as a graphic novel we agreed only on the condition that we have the liberty to completely change the story and premise. Neither of us were interested in doing another story about psychopaths in straight-jackets and padded cells. We talked about it and wondered: What would it really take to try and find a cure for something like psychopathy? That question led us down a path that forced us to rethink the whole idea of a “hospital for the criminally insane” and that, in turn, suggested to us the characters, stories and themes that would ultimately become Syndrome in its current form.

DQ: When we heard they wanted to do SYNDROME as a graphic novel we agreed only on the condition that we have the liberty to completely change the story and premise. Neither of us were interested in doing another story about psychopaths in straight-jackets and padded cells. We talked about it and wondered: What would it really take to try and find a cure for something like psychopathy? That question led us down a path that forced us to rethink the whole idea of a “hospital for the criminally insane” and that, in turn, suggested to us the characters, stories and themes that would ultimately become Syndrome in its current form.

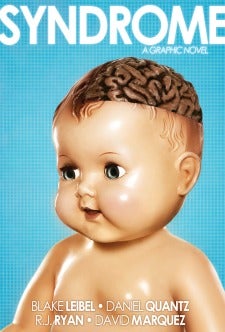

RJR: We were given the task of finding the artist on the project, David Marquez, as well as our cover artist, Michael Dahan, who is a photographer and a former feature film executive at the Mark Gordon Company, where Dan and I worked years ago. The cover turned out great — it's such an unusual image for a graphic novel, and it came out of endless talks with Michael about how to do something that looked like no other comic book cover out there. I think the positive reviews and reaction we've gotten so far is a response to the fact that David is a really new and interesting voice in comics and the underlying material is unexpectedly strong. We got very lucky that the three of us had some chemistry as a creative team.

How is writing for sequential art different from writing a screenplay?

DQ: It requires an entirely different way of thinking about storytelling. Instead of using the passage of time to tell the story as you do in film, you have to control space instead. There is a lot more that happens in the mind of the reader, so it’s a constant challenge to make sure they have all the information they need, but not too much. You’re also obliged to be a lot more specific in your direction to the artist than you ever would in a screenplay. The artist creates the performances, set design and cinematography so it’s important to give them as much direction as necessary.

Steve Kornacki Exits MSNBC for NBC

RJR: Writing comics kind of forces you to be a "producer" as well, just in the sense that you have to work closely with the artist and with our editor at Archaia, Stephen Christy, to fulfill the vision of the initial script. I think comic book writing is a bit more like TV writing than feature film writing, in the sense that the onus is on the writer to kind of pull everything together and lead the project. That doesn't happen a lot with movies but it's pretty much the case with every successful TV show. We took our responsibility in that regard really seriously and we're proud of how the package came together.

RJR: Writing comics kind of forces you to be a "producer" as well, just in the sense that you have to work closely with the artist and with our editor at Archaia, Stephen Christy, to fulfill the vision of the initial script. I think comic book writing is a bit more like TV writing than feature film writing, in the sense that the onus is on the writer to kind of pull everything together and lead the project. That doesn't happen a lot with movies but it's pretty much the case with every successful TV show. We took our responsibility in that regard really seriously and we're proud of how the package came together.

One of the special things about this book is that it's never existed as a "floppy" stapled comic book — it was conceived right from the start of the process as the meaty, twenty-dollar oversized hardcover it is — with really top-flight production values. Archaia as a company is really special in the sense that they work more like a prose book publisher and it's not just about monthly sales, it's about a title that can have a real shelf life. We sold twice as many books in the second month of release as we did in the first because SYNDROME sits on the shelf a lot more nicely and permanently than a "magazine"-style comic. It's a book we want people to keep buying and discovering over time and so far that's exactly what's happening.

What was the best part of writing this graphic novel?

RJR: Finishing it, and putting it in people's hands. We worked for more than a year on it before it was even announced, and it was hard to not talk about it in detail to our friends and people we know in the media. We really wanted to surprise people with the subject matter and of course with the very special work David, our artist, did. It's very tricky in the comics world to close yourself off from other work for such an extended period of time, but SYNDROME feels like it was worth all the attention we had to give it. Making the book was overwhelming, but in a good way.

RJR: Finishing it, and putting it in people's hands. We worked for more than a year on it before it was even announced, and it was hard to not talk about it in detail to our friends and people we know in the media. We really wanted to surprise people with the subject matter and of course with the very special work David, our artist, did. It's very tricky in the comics world to close yourself off from other work for such an extended period of time, but SYNDROME feels like it was worth all the attention we had to give it. Making the book was overwhelming, but in a good way.

What’s next for the two of you?

RJR: We're both working on new projects, mostly in the TV development world, but we both have new graphic novel properties on the burner. We've also managed stayed involved and tied to SYNDROME as a piece of intellectual property, both in future comics, which people keep telling us they want, and in case it does wind up turning into something in other media. But we're we aware of how unlikely that is — it's literally a one in a million shot for that kind of thing. We were focused like lasers on making the book stand on its own. In this marketplace, it has to.

DQ: We have completed work on another comics project that involves a lot of popular comic book writers and which was announced last year, but our involvement hasn't been publicly disclosed yet, so that news will have to wait until closer to that book's release.