In their new book “The Curse of the Mogul,” a trio of academics take aim at the business of Hollywood and big media.

Their conclusion: It’s the moguls’ fault.

It’s their fault that media companies are inefficient, that executives are overpaid, that they fail to increase shareholder value — and that their acquisitions are ego-boosting destroyers of value that achieve no real synergies.

“The shocking, evident, persistent and oddly ignored fact is that the financial returns of media companies significantly and relentlessly falls below those of the stock market as a whole,” the authors write in their “the emperor has no clothes”-toned introduction. (They are Columbia Business School professors Jonathan Knee and Bruce Greenwald, and media consultant Ava Seave.)

“For all the excitement, glamour, drama and publicity releases they produce, why can’t these companies come close to delivering the kind of returns available from closing your eyes and throwing

a dart?”

Ouch. The evidence they offer is further wince-inducing:

For most every recent 10-year period – and they settled on 1995-2005 as their sample — media conglomerates achieved less than one third of the returns available from the S&P, “and none of them came closer than 400 basis points (4%) of this benchmark.”

Between 1995 and 2005, the shareholder returns were, for:

News Corp 5%; Viacom 3%; Disney 2.6%; Time Warner -.7%.

That makes an average of 2.5% — compared to a 9% rise in value for the S&P.

This is the kind of hard evidence that Hollywood doesn’t like to look at.

This is the kind of hard evidence that Hollywood doesn’t like to look at.

And on the face of it, it does seem strange. We in the media have long written about the fact that media and entertainment companies are now run by the dictates of Wall Street, rather than the demands of either the consumer market, or the long-term visions of the legendary moguls of yore, who used to run major studios like MGM and Columbia decades ago.

(And by the way, they ran those companies as supremely profitable enterprises. That’s because they and their families owned them.)

So it is a rare and and welcome analysis that brings these numbers out into daylight, measuring media companies by the drab metrics of shareholder value and not, say, by the number of weekend wins at the box office or the number of photo ops with Johnny Depp.

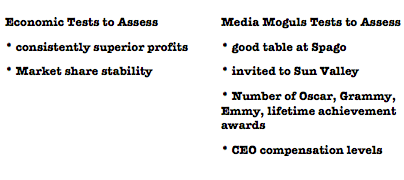

(The authors have some fun with tweaking perception of value versus shareholder value; see the chart above.)

They do acknowledge that media companies hit the S&P level from 1990-2000, during the Internet bubble, “but for every other 10-year period, the conglomerates meaningfully underperformed.”

Their critique is especially worth considering as media companies face a brutal and fast-changing landscape, with another major acquisition, Comcast and NBC-Uni, on the horizon.

So does this mean that shareholders ought to divest themselves of media companies ASAP, before Comcast sins again?

Well, hold on a minute there.

Media companies are actually not like all other companies. That may be heresy for Columbia Business School professors, but it is undeniably true.

There is an unquantifiable, but absolutely valid, value that media companies represent, and that makes them so desirable: influence. Influence over public taste, over consumer trends. Engagement and influence over popular culture. Influence over the flow of information, access to newsmakers.

It’s not just about being able to attend the Oscars, though that’s certainly an enduring draw.

The authors make the mistake of looking at the public popularity of media companies, and concluding that fear is the propellor behind that. They write of the “peculiarly American paranoia about the media industry’s ability and inclination to mold the national psyche.”

The authors make the mistake of looking at the public popularity of media companies, and concluding that fear is the propellor behind that. They write of the “peculiarly American paranoia about the media industry’s ability and inclination to mold the national psyche.”

It’s not paranoia. It’s a reality. That is largely the reason why media companies remain as sexy and relevant as they are – even in the miserable down market they now face.

The authors' argument is poorly supported as it pertains to the moguls themselves.

Strangely, they use former Vivendi CEO Jean-Marie Messier – who owned a U.S. entertainment company , NBC-Universial, for all of three years – as their textbook case of a bad mogul.

And they use Lew Wasserman, arguably the most iconic Hollywood mogul in the latter part of the 20th century – as the example of an atypically good mogul.

They cite Wasserman as the exception to their generalization of Hollywood profligates – someone who worked his business with great efficiency, tight financial controls and a keen eye to the bottom line.

That undermines the title of the book, in my view. If Wasserman is the exception, and Messier the interloper is the rule – then they have the wrong definition of a mogul.

Tomorrow: Why Content Isn’t King, and How Hollywood Missed the Memo on Acquisitions