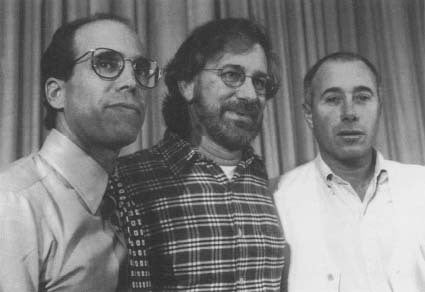

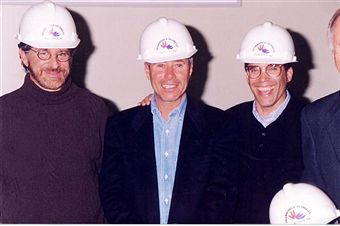

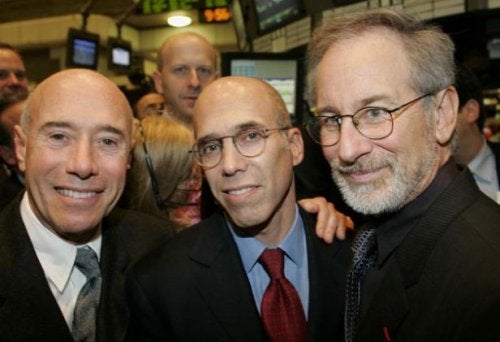

The scope and breadth of DreamWorks’ ambitions reflected the go-go nineties — a time when the economy was surging, Bill Clinton was in the White House, and a still mysterious resource known as the World Wide Web was about to change everything. But its expansiveness was also reflective of its resident rainmaker: director Steven Spielberg.

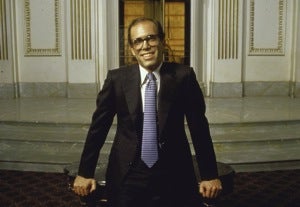

It was not because of former Disney über-executive Jeffrey Katzenberg, or David Geffen, the billionaire music impresario, that DreamWorks — the first Hollywood studio to be formed in 60 years — was getting into the videogame business or mulling over the creation of entertainment centers where families could chow down on hamburgers and zap space invaders (what would be known as GameWorks).

The company was molded around the ideas and dreams of its resident man-child, the inspiration for DreamWorks’ newly unveiled logo: a little boy sitting on the edge of the crescent moon, casting his fishing line into the stars. Whenever a wish materialized in Spielberg’s endlessly imaginative mind, it was up to Geffen and Katzenberg to wave their magic wands and make it come true.

Katzenberg gave no indication of being upset by his exclusion from live action, but according to a longtime friend, he was deeply pained. “He’d never admit it, but absolutely,” this person acknowledged.

Katzenberg gave no indication of being upset by his exclusion from live action, but according to a longtime friend, he was deeply pained. “He’d never admit it, but absolutely,” this person acknowledged.