As I write this, I realize I am about to do something that, for the most part, is never done. I am going to criticize a critic.

Filmmakers are never supposed to respond to a critic about their work. It’s an unspoken rule of engagement. But in this case, I feel compelled.

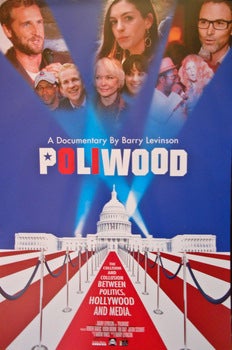

I am going to criticize Alessandra Stanley, the TV critic for the New York Times. I am not going to criticize her on the basis of what she may not like about my recent film essay “Poliwood,” but I am going to take her to task for her blatant inaccuracies. For her inability to view the piece for what it was.

It may be true that I am overly sensitive to her critical writings ever since reading a review she wrote some time ago about a Walter Cronkite documentary that was part of PBS’ “American Masters” series. I had nothing to do with that project other than to see it and to read her review, which began, “There will never be an anchorman like Walter Cronkite. And thank heaven for that.”

It may be true that I am overly sensitive to her critical writings ever since reading a review she wrote some time ago about a Walter Cronkite documentary that was part of PBS’ “American Masters” series. I had nothing to do with that project other than to see it and to read her review, which began, “There will never be an anchorman like Walter Cronkite. And thank heaven for that.”

It was a shocking opening line — an assessment that I would certainly disagree with — but nevertheless, she is allowed to express her own opinion.

However, the line that really caught my ire for its blatant inaccuracy was what she said about Cronkite informing the nation about the assassination of President John Kennedy: “He informed and consoled the nation with stoic grace. But it’s hard to imagine that anyone in that chair at that moment, wouldn’t have been just as memorable, simply because he was there.”

Anyone in that chair! Anyone? The impression you get from Ms. Stanley is that there was only one network and one person reporting this event back then. Is she suggesting that Walter Cronkite was the only reporter informing us about this assassination?

The reality is there were three networks and they were all reporting the event, and Walter Cronkite is the only one we remember.

Why do we remember Cronkite as he took off his glasses on that tragic day and reported that the young president had just died? According to Ms. Stanley, it had nothing to do with Cronkite’s unique ability as a newsman or his special ability to connect with an audience. It was because he was the only one there, reporting.

To defend her thesis she had to carefully eliminate two networks from history — and two chairs.

Yet this is what Ms. Stanley does: She alters reality to fit her thesis. It is blatantly inaccurate and deceitful. It is a bogus sentence, illogical and fraudulent.

That is not valid criticism, and should have no place in such a respected paper as the New York Times. But it was written, and it was printed.

Now I come back to “Poliwood.”

Ms. Stanley states, “In politics, the only thing worse than no access, is too much access.” She goes on to say, “At its core the film is a screed about everything that was wrong with politics and media during the 2004 election, carried over and misapplied to the 2008 campaign.”

For the record, the film essay has nothing to do with the 2008 campaign. That’s why there is no footage of the candidates leading up to the conventions, and no footage of them campaigning on the road, leading up to the election. There is also no footage of the candidates stating political positions. No footage of strategy sessions. No discussions with the political operatives of either side. No footage of the fears or anxieties, the second-guessing, the tiresome campaign trail.

I cover the two conventions and the inauguration merely as the backdrop for the intersection of politics, media and entertainment as the cameras followed the journey of the Creative Coalition through these events.

It was not a case of too much access, as Ms. Stanley suggests. I had no access to either campaign. I never asked for nor was refused any such request for the one simple reason: I wasn’t filming a campaign. It was not the point of the piece.

I don’t wish to cherry-pick a critical line of hers from within her overall review, but it is the opening sentence.

At another point, Ms. Stanley states that my observations about the media were incorrect because the media did not determine the outcome of the 2008 election. Like her previous comment, the fact that Obama won was not the point of the piece. That’s for other filmmakers to make.

But “Poliwood” does address the importance of telegenic (TV-friendly) political figures, of which Obama is one.

Is Ms. Stanley suggesting that Obama’s attractive appearance, his ability as a great speaker, his youth and vibrancy, and his story of rising from poverty as shown on television had absolutely no effect on him becoming president?

The film is much more of a sociological look at the cause and effects of television, the good and the bad and the sometimes ugly as it applies to the political dialogue. Not the 2008 election. But Ms. Stanley writes, “Poliwood gets on the bus with a group of politically minded movie stars, and forgets to get off and on to the campaign.” We didn’t forget. It was not the point of the film essay. There can only be two reasons for her fraudulent statement: one is that her arrogance is only exceeded by her ignorance, or two, since she was also reviewing By The People, a documentary that did follow the campaign, she needed to blend the two pieces to fit her own critical agenda.

Ms. Stanley can be as critical as she wants of Poliwood, but I find it very disconcerting to be criticized for what wasn’t presented so she can fuel her own false premises.

To reiterate, criticism is a part of a filmmaker’s journey. Any time you attempt to tackle a subject that is complicated, one is open to criticism. It comes with the territory. A WARNING: to any thin-skinned filmmaker, get out of this line of work quickly or you’ll die a hemophiliac. But when one’s work is used as fodder for a critic such as Ms. Stanley, then I feel I must speak up…and throw caution to the wind. I know the old adage, “Never get into a battle with someone who orders ink by the gallon,” but I can’t help myself.

The New York Times is known throughout the world as one of the leading newspapers in this country. It has excellent film criticism and book reviews. And a very strong op-ed page. Where Ms. Stanley fits into this strong lineup is questionable at best.

As a filmmaker, all you can expect is for your work to be examined for what it is. I keep thinking of Walter Cronkite at the end of his life, reading Ms. Stanley’s quote. “There will never be an anchor like Walter Cronkite. And thank heaven for that.” And I wonder after reading that devastating comment, whether he thought to himself: ‘Ms. Stanley, what exactly did I do that was so wrong?’

And just for clarification, Walter Cronkite did not say that. I just made it up. Clarity is important.