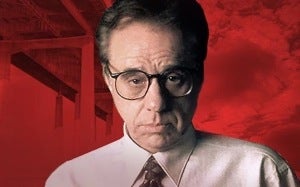

Equally renowned for his high-wire personal life and his dizzying success as a film historian, actor (Dr. Melfi’s shrink in “The Sopranos”), writer and Academy Award-nominated director (“The Last Picture Show”), Peter Bogdanovich comes to California this week as part of the Turner Classic Movies Road to Hollywood Tour and the TCM Classic Film Festival. Bogdanovich gained widespread critical and popular acclaim for directing films such as “Paper Moon” and “Mask,” but fell from grace after a series of personal calamities and professional missteps.

He spoke with Eric Estrin about Stella Adler’s “Brilliant, darling,” being a one-man show for Roger Corman and squeezing it out of Boris Karloff.

He spoke with Eric Estrin about Stella Adler’s “Brilliant, darling,” being a one-man show for Roger Corman and squeezing it out of Boris Karloff.

I started as an apprentice and an actor in a children’s theater in Traverse City, Michigan, in the summer of ’55 – the summer I turned 16 — and then I moved up and got some leading roles in the major productions before the end of the summer.

So when I got back to New York, where I lived, I started studying with Stella Adler. You weren’t allowed to study with Stella unless you were 18, but I lied about my age. I studied with her for four years while I finished high school.

All that time I was planning to be an actor. But at some point toward the end of my tenure at Stella’s, I was sitting with a bunch of actors and I said, I’d like to direct you guys in a scene, for scene class. We picked something out of Clifford Odets’ “The Big Knife,” which is significant to me because it was about Hollywood.

You never had more than two people for a scene in scene class. But suddenly five guys got up on stage and did this for Stella, and she stood up afterwards and said, “Brilliant, darlings, brilliant! But you’ve been directed. Who directed you?”

They pointed at me, standing in the back. She said, “Brilliant, darling, bravo!”

So that was it. That was the note that opened up a whole new avenue for me.

One of those actors had a connection with Odets and gave me his address in Hollywood. I wrote to him an impassioned letter asking him to let me do “The Big Knife” off Broadway. He’d never allowed anybody to do any of his plays off Broadway – but miraculously, I get a letter back about two weeks later — on Fox stationery — giving me the rights.

It took me nine months to raise the $15,000 I needed, and we put it on, and it ran about 70 performances. I was hoping to be discovered to make movies, but it didn’t happen.

It took me nine months to raise the $15,000 I needed, and we put it on, and it ran about 70 performances. I was hoping to be discovered to make movies, but it didn’t happen.

Years later, I was writing for Esquire about film, I was writing monographs and curating film retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art; I did a piece for the Saturday Evening Post; I did pieces for TV Guide; I was making a living as a writer, waiting to either do another play or to get into the movies.

About that time, Frank Tashlin, the director, whom I’d met when I interviewed Jerry Lewis for an article, came through town and he came up to my apartment. He said, “Well what do you want to do? Do you want to direct plays or do you want to direct movies?” And I said, “Well, I really want to direct movies.”

So he said, “Then what the f— are you doing in New York? They make ’em in California.”

Six months later, with no money, I moved to Los Angeles and got a little house in the San Fernando Valley.

A year later, a mutual friend introduced me to Roger Corman at a movie. And he said, “I’ve read your stuff in Esquire; you’re a writer. Would you be interested in writing a movie?”

He was preparing a movie called “All the Fallen Angels.” Eventually it became known as “The Wild Angels,” with Peter Fonda and Bruce Dern. He didn’t like the script, and he wanted my opinion.

I read it and I told him I thought it was dreadful. He said, “That’s what I think; would you do a rewrite? I can’t give you any credit and I can only give you $300.” So for $300 and no credit, I rewrote 85 percent of the script.

He liked what I did, so he asked me to look for locations for it. And then he liked what I did for that, so he asked me to be his assistant on the picture. So I worked 22 weeks on “The Wild Angels.” It became the most successful movie in Roger Corman’s career. It cost $300,000 and it grossed $6 million, which was in those days a huge amount. And so he offered me a picture to direct on my own, with a lot of caveats.

The basic limitations were, I had to use Boris Karloff, who owed Roger two days’ work. I had to shoot 20 minutes of Karloff in two days, use 20 minutes of Karloff from another picture of his called “The Terror.” That would give me 40 minutes of Karloff. Then shoot with a bunch of other actors for 10 days — shoot another 40 minutes with the other actors, and then he’d have a new, 80-minute Karloff picture. That was the assignment.

It turned out differently. We wrote a script that he liked very much. I had a lot of help from Samuel Fuller, who was a friend by then. And Roger eventually paid Karloff for an additional three days, so I had Boris for five days. We shot the rest of the picture in 18 days, and it became a thing called “Targets,” which I then sold to Paramount for a low amount, and Paramount half-heartedly distributed it. But it became a cult picture and it’s still out there on DVD.

That was officially my first feature. That got got mixed reviews, but it got a lot of attention, and I was suddenly an up-and-coming young director, having written and directed and produced and acted in my first picture.

It was shown to a company called BBS, which had just produced “Easy Rider” and “Five Easy Pieces” for Columbia, and they said, “If there’s anything you want to make, we’d like to do business with you.”

So through a series of strange coincidences, again, I read a book called “The Last Picture Show” and suggested that I’d like to make that. They read it and said OK, let’s make it, and we did.