Hollywood seemed like another world to Ashok Amritraj when he was a boy, but his world-class tennis skills gave him a passport to success — and his love of American movies ultimately drove him to produce more than 100 of them (“Bringing Down the House,” “Shopgirl”). As chairman of Hyde Park Entertainment, he recently committed to financing and producing a new series of films based on Andy McNab’s Nick Stone novels set in the world of British Intelligence.

Amritraj spoke with Eric Estrin about playing bad Hollywood tennis, doing business out of the Polo Lounge and going independent with the aid of Roger Corman.

Amritraj spoke with Eric Estrin about playing bad Hollywood tennis, doing business out of the Polo Lounge and going independent with the aid of Roger Corman.

Growing up in India in a city called, at that time it was Madras, now it’s called Chennai, I watched the Hollywood movies that used to come there. I fell in love with “Sound of Music,” “Ben Hur,” and the great older films. But, you know, the family business was tennis, and I played professionally all through the ’70s.

In ’75, after I reached the finals of the Wimbledon Juniors, Jerry Buss brought me out here, and I played for the Los Angeles Strings. In ’78, we won the World Team Tennis championship with Ilie Nastase and Chrissie Evert, and I was MVP that year.

Jerry was very much a part of Hollywood society. So I met a lot of producers, directors, studio executives … I met Charlton Heston, Sidney Poitier, Gene Wilder, Mel Brooks, Garry Marshall, Sherry Lansing — a whole host of people.

Around the latter half of 1980 I talked to some of them about going into their business. One might think being a tennis player was a great plus, because I knew a lot of people in town. But as a sportsman, they don’t take you very seriously. They say, well, this guy’s gonna be around for about six months.

So I ended up playing in a lot of tennis games with studio executives and stars. Actually, a lot of bad tennis games. And it took me a while to realize that while Hollywood would love to play tennis with me, it did not necessarily want to make a film with me.

I had a little bit of money, and my idea was to option a couple of things that were interesting and high profile. So I opened an office, and I did business between the office and the Polo Lounge, where I’d hang out just to be visible.

At the same time, I continued with my tennis. My parents thought I was completely nuts, because I was playing at Wimbledon and the U.S. Open, and here I was taking this step into a completely alien business.

Eventually, I managed to get an option on a great property, a remake of the musical “Damn Yankees.” It was a great moral tale, and I was fascinated by it. So I pitched it to Ned Tanen at Universal. He loved it but told me to go and partner with a real producer on the studio lot.

So Bernie Schwartz, who made “Coal Miner’s Daughter,” and I ended up partnering. It was the first picture I ever developed, but it didn’t end up going. It got put into turnaround about two years later.

I had a similar experience at Fox. You know, it was a tough five years for me. After a couple of these tries, where I developed films at the studios and none of them went forward, I sort of changed horses. In ’85, I raised a little bit of money, and for half a million dollars, I went out and made a movie in Arizona.

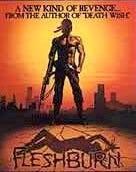

It was from a book by a fellow called Brian Garfield, who had earlier written the novel “Death Wish.” This was a lesser known book called “Fear in a Handful of Dust,” and we made it as “Fleshburn,” with Steven Kanaly, before he was on “Dallas.”

I had been to a couple of movie sets and editing rooms with people like Sidney Poitier, and I had tried to hang around to sort of see what they were doing. But this was really the first experience getting a movie made.

It was my real start. For the next four or five years I made movies with Hemdale; I made about six with Roger Corman, like “Black Thunder” and “Beneath the Bermuda Triangle.” It was a perfect time because the video market was very strong. Though these movies were released in theaters, the primary market was really video — they were selling for like 80 bucks. It was a different world, and there was a real place for independent movies.

I made about 20 movies at that time, and it taught me about production and how to stretch the dollar, while at the same time I started to understand how important the international market was. You kind of had to do it all — put it together, finance it, produce it and work on the post-production, and then make sure it was distributed properly.

So it was an overall great learning ground for the bigger films.